Show, don’t tell (blah, blah, blah!)

Illustration by Tim Martin

I like pictures. Not all pictures, mind. I don’t understand a great deal of modern art when it’s a large canvas covered in one or two colours, and people are enthused about the brushwork. What’s that nonsense all about? I like illustrations that involve people and a sprinkle of humour. You can see examples of my illustrations on my website.

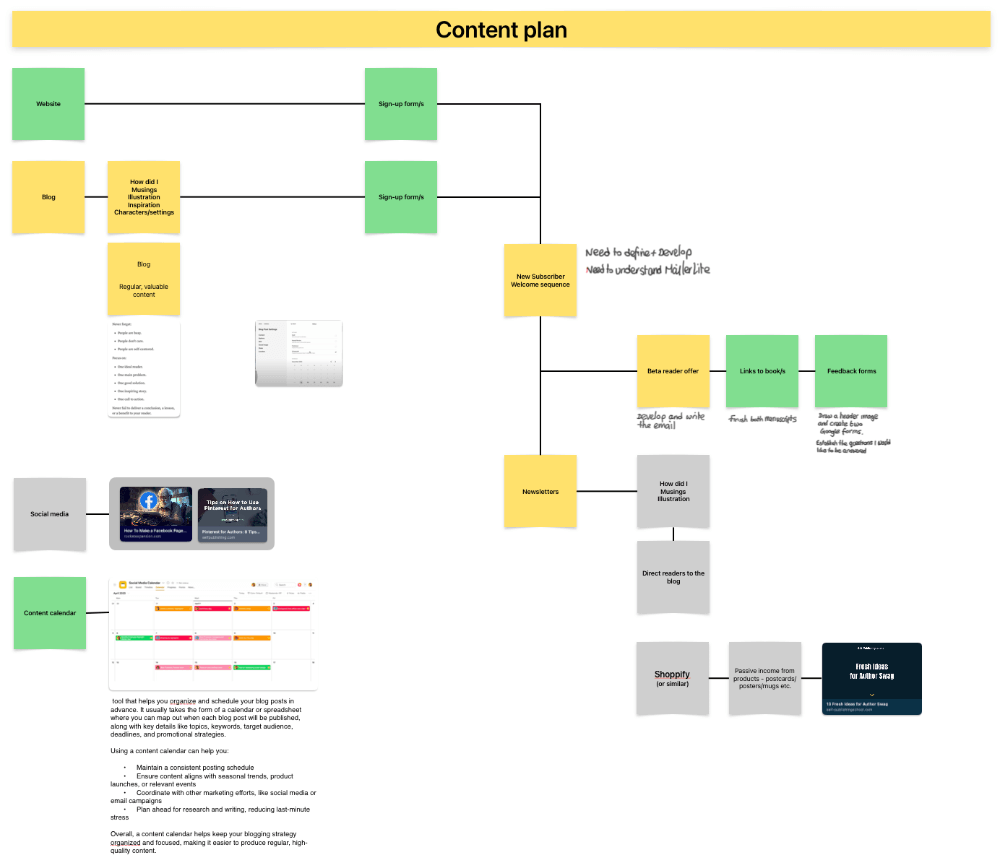

I am a visual learner. At work, I am forever drawing diagrams, flowcharts, and graphs to help me interpret, digest, and then to communicate ideas and information. I draw a line at pie charts, though. They make no sense to me, especially when there are over five segments. For me, pictures do speak a thousand words. As an example, this is an Apple Freeform board for how I intend to market myself and my writing. Now imagine describing this diagram in written form.

Diagram created in Apple Freeform by Tim Martin

The business world is committed to long documents and reports that the author hopes are read, understood, and achieve what they set out to achieve. Let me tell you, it’s painful to describe things such as the image above in words, and reading them is as painful … for me, at least.

I struggle with books in the literary fiction genre. Occasionally, it is the sheer length and density of the text. At other times, it is the verbosity of the writing or the way the story is told. I love to lose myself in the story and can picture everything that is happening, but when the writing might include all five senses to describe biting into a carrot, it gets too much.

I lean away from literary fiction and lean into short(ish) stories that are fun, easy to read, i.e., no dictionary required, and full of dialogue. In a future post, I’ll offer examples of my favourites.

Show, don’t tell

How does someone like me move into writing fiction? If you read about writing, you will come across the phrase Show, don’t tell. The premise is that telling the reader what is happening makes for a boring story. It is better to show the reader what is happening. Showing is more descriptive and allows the reader to visualise a scene. This is where my aversion spider senses begin to tingle. Again, five senses and a carrot. These are a few simple examples:

Tell: He walked

Show: He ambled along, kicking loose stones …

Tell: He drank

Show: He gulped the orange liquid, gasping as the last drops dripped from his chin.

Tell: He ate

Show: He wolfed the food, finishing before his guest had figured out how to hold the chopsticks.

Tell: He was angry

Show: His fists balled, and his brow furrowed. He squared up to …

The premise is that showing makes for a better story. This is difficult to do when you have spent your life writing business documents where telling in simple, logical words and ways (littered with business jargon and acronyms) is the norm. It is a world where your vocabulary, outside acronyms, is limited to, say, eight hundred to one thousand words. The Oxford English Dictionary contains somewhere near five hundred thousand words.

Blah, blah, blah!

I read a book named Blah, Blah, Blah: What to Do When Words Don’t Work by Dan Roam. I cannot express to you how much I loved it. It describes how the brain commits information to memory and how, since cavemen, we have drawn images to communicate, and a test of describing the safety of a chair with three legs. It resonated with me because it showed how words and pictures could be better used together. But now I have begun writing fiction, it has made me think about how I write in a Show, don’t tell way.

Another book I adore is The Sketchnote Handbook by Mike Rohde. I so wanted to introduce the techniques from these two books into my work, but Local Government is not ready for it. Can you imagine if policies and strategies were brought forward in the form of a few pictures of stick people doing things rather than tens of pages of dense text in multiple languages and with acronyms galore? Nope. Can you imagine if the Male and Female signs on toilet doors were not pictograms but written dictionary definitions?

What am I rambling on about here?

Writing novels is hard. Literary fiction novels must be incredibly difficult. I listen to the wonderful In Writing podcast by Hattie Crisell. In an episode from 22nd November 2024, Hattie interviews the novelist Tom Crewe. He indicates he has been writing his second novel since the beginning of 2022 and is nowhere near finished. He then discusses his work for the London Review of Books (LRB) and how he dislikes unintended rhymes, where two sentences in a paragraph may end with ‘no’ and ‘go’. I hear how authors are happy if they write five hundred words per day. This post is over one thousand words. This level of focus and attention to detail is commendable but is not something I could bear to think about. I want to tell a story, even if the writing is at the level of a pre-GCSE student compared to a renowned author of literary fiction.

Say what you see

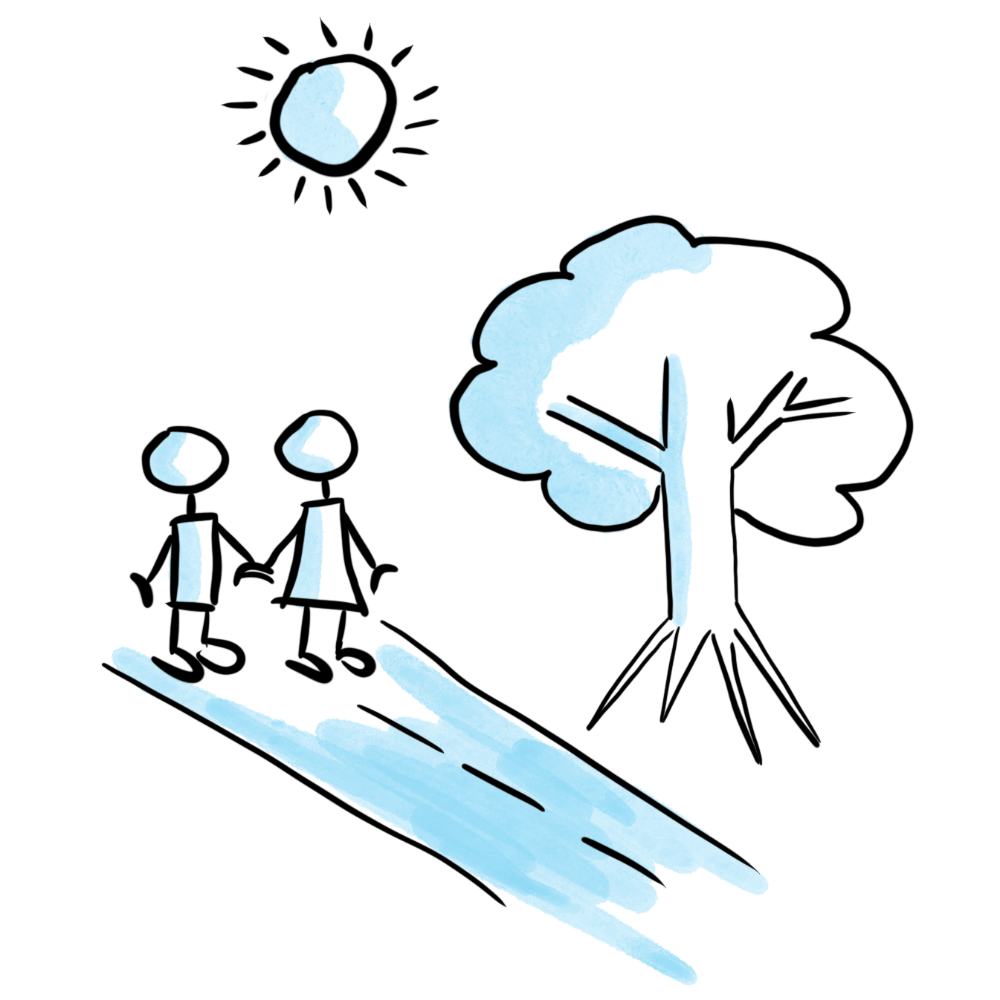

This is my example by way of comparison of these methods.

Illustration by Tim Martin

Say what you see…

Now consider how it might be interpreted and translated for a business report — Tell.

In the diagram, the scene is of a sunny day with a couple walking along a road. They are holding hands as they pass a tree.

Now, how I imagine this might be written for fiction — Show.

They sauntered along the gritted and pockmarked road. Their fingers entwined: warm and uncomfortable, with sweat forming between their palms and the joints of their fingers. A blazing sun and the cloudless, endless expanse of cerulean. The horizon always unreachable, but they didn’t care. The gnarled oak tree danced and bowed in reverence as they paraded past.

So that’s my GCSE-like interpretation of the study of Show, don’t tell. Now, if you are going to write fiction, the topic cannot be avoided. One has to work out the best way to use or break the rules to suit your style. To hope someone likes it and not laugh you out of (literary) town.

My writing style is full of colloquial dialogue that is used to move scenes forward rather than long passages of description or exposition. The dialogue is my way of injecting what I see (my pictures, my sketchnote, my blah, blah, blah) into the story. This is how I might write about the diagram.

“Christ, it’s hot. I can’t hold your hand any more. I love you, but clammy hands are a bit of a turnoff. Sorry,” she said.

He let his hand drop and wiped it on his jeans. “Yeah, I was thinking the same. My arse crack is sweating buckets. Do you want to sit under this tree for a bit? We’ve been walking for ages, and my feet are killing me.”

There we are. I think in pictures, and I write in a conversational, episodic way (lots of short chapters). I am uninterested or incapable of writing a chapter, let alone a whole book, in what I perceive to be a literary fiction way, and I rarely know if I am showing or telling. If my style of storytelling interests you, then why not check out my books.

If you want to follow along, why not sign up for my newsletter, where I will summarise what I have learned or done. I’ll produce something once per month, and I promise I won’t spam your mailbox.

If you fancy reaching out, why not contact me.